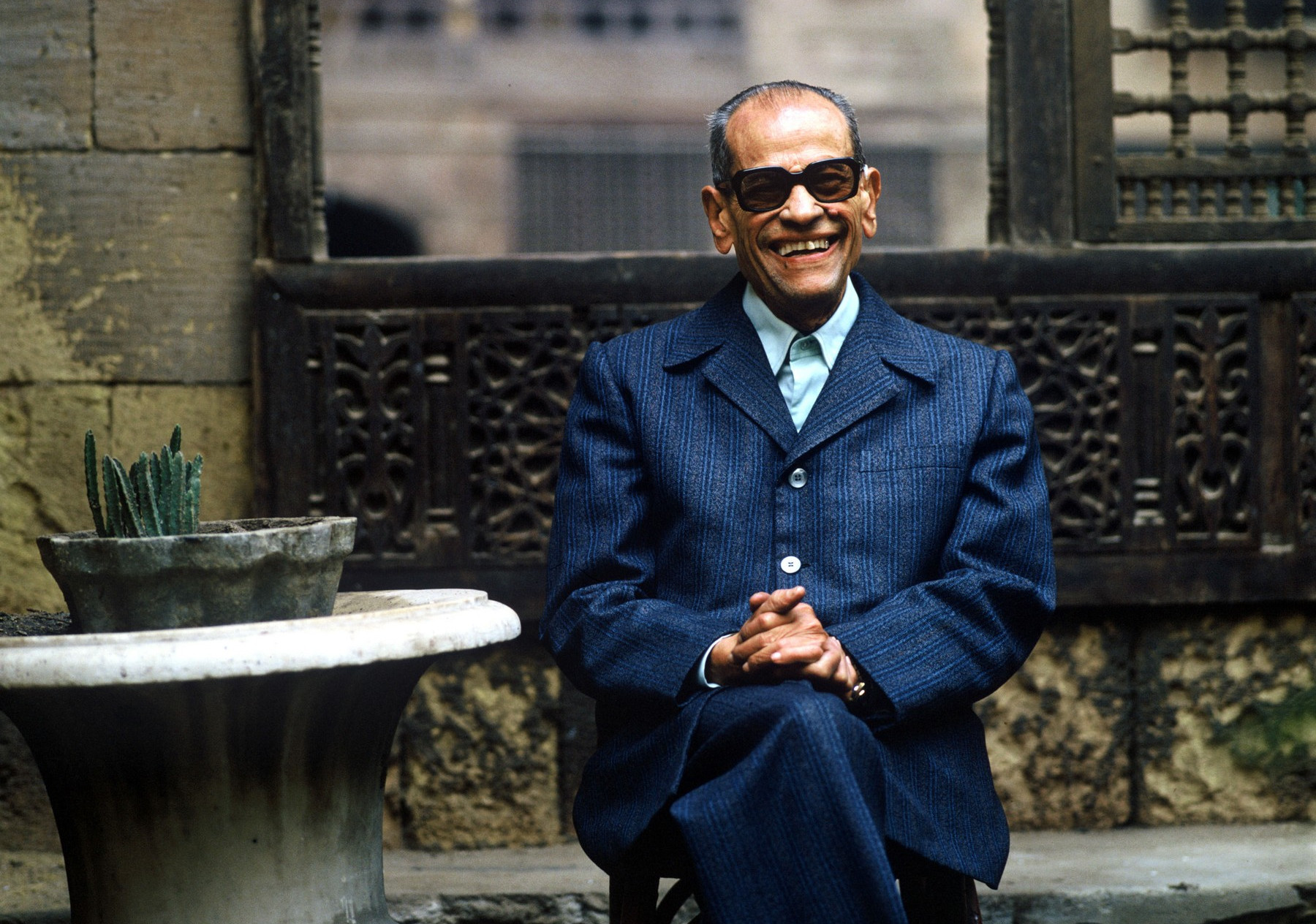

This tour is dedicated to the Egyptian writer who had won the Noble Prize in 1988, Naguib Mahfouz (born in 1911 & died in 2006). Mahfouz was in Cairo’s famous old Gamaleyya district. He attended the Egyptian University (now Cairo University), where in 1934 he received a degree in philosophy. He first worked as a bureaucratic clerk for several years before he dove into the craft of novel writing.

Mo Swefy Tours

We will start our tour just in front of the main entrance of Al-Azhar mosque the oldest surviving Islamic University in the world since 969 AD. Which is facing Abul-Dahab complex that contains the Modern museum of Naguib Mahfouz in it.

First we will visit his museum and see his Nobel Prize of literature. Then we will move on to view Sultan Al-Ghuri’s archaeological complex (1501-04 AD). We’ll continue to the Fakahani (the fruit seller) mosque and the Sabil-Kuttab (Fountain-School) of Muhammad Ali Pasha’s son Tusun (1820 AD).

Followed by a visit to Sultan Muayyad mosque (1420 AD) and the renowned Bab Zweila gate of Cairo (969 AD). On the way, just in the corner before the gate there’s the famous Sugar Street of Naguib Mahfouz’s triology.

Finally We’ll take a vehicle to the Northern area of Fatimid Cairo (just a 10 min ride) “El Gamaleyya District” the birth-place of Naguib Mahfouz where we can see his first home and a big medieval collection of Mamluke monuments nearby, such as but not limited to: Qalawoun complex, Barquq college-mosque, and al-Nasir Muhammad son of Qalawoon’s madrasa.

Here we’ll be right

at Bein al-Qasrein (the Palace-Walk) also a vital component of the Cairo

Trilogy of Mahfouz.

An up-close photo of the main entrance of Al-Azhar mosque.

We’ll continue to see Qasr al-Shoq (Palace of Desire) from his trilogy as well, and eventually we’ll end our tour at Al-Azhar street, where you can take Uber to get you back to our home or just wander a bit by yourselves in the adjacent Market of Khan El-Khalili, or even decide to have your lunch somewhere.

Mahfouz’s earliest published works were short stories. His early novels, such as Radobees were set in ancient Egypt, but he had turned to describing modern Egyptian societal culture by the time he began his major work, the series known as The Cairo Trilogy. Its three novels—Bayn al-qaṣrayn (Palace Walk), Qaṣr al-shawq (Palace of Desire), and Al-Sukkariyyah (Sugar Street)—depict the lives of three generations of different families in Cairo from World War I until after the 1952 military coup that overthrew King Farouk. The trilogy provides a penetrating overview of 20th-century Egyptian thought and culture.

Dinner Cruise on the Nile River with EntertainmentIn 1988 he became the first Arabic writer to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

He published over 50 novels, over 350 short stories, dozens of movie scripts, and five plays over a 70-year career. Many of his works have been made into Egyptian and foreign films. Like “El Callejon de Los Milagros, starring Salma Hayek”.

Naguib Mahfouz’s writing deals with some of life’s essential questions, including the passage of time, society and norms, knowledge and faith, reason and love. He often uses his hometown of Cairo as the backdrop for his stories and only a few of his early works are set in ancient Egypt as we may have mentioned earlier above.

Bab Zweila, the southern gate of Fatimid Cairo (known as Islamic Cairo in the English guide books).

Mahfouz was born in a lower middle-class

Muslim Egyptian family in Old Cairo in 1911. He was the seventh and the

youngest child, with four brothers and two sisters, all of them much older than

him. (Experientially, he grew up as an “only child.”) The family

lived in two popular districts of Cairo: first, in the Bayt al-Qadi

neighborhood in the Gamaleya quarter in the old city of Cairo, from where they

moved in 1924 to Abbaseya, then a new Cairo suburb north of the old city,

locations that would provide the backdrop for many of Mahfouz’s later writings.

His father, Abdel-Aziz Ibrahim, whom Mahfouz described as having been “old-fashioned”, was a civil servant, and Mahfouz eventually followed in his footsteps in 1934. Mahfouz’s mother, Fatimah, was the daughter of Mustafa Qasheesha, an Al-Azhar sheikh, and although illiterate herself, took the boy Mahfouz on numerous excursions to cultural locations such as the Egyptian Museum and the Pyramids.

The Mahfouz family were devout Muslims and Mahfouz had a strict Islamic upbringing. In an interview, he elaborated on the stern religious climate at home during his childhood. He stated that “You would never have thought that an artist would emerge from that family.”

The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 had a

strong effect on Mahfouz, although he was at the time only seven years old.

From the window he often saw British soldiers firing at the demonstrators, men

and women. “You could say … that the one thing which most shook the

security of my childhood was the 1919 revolution”, he later said.

In his early years, Mahfouz read extensively and was influenced by Hafiz Najib, Taha Hussein and Salama Moussa, the Fabian intellectual.

Al-Muiz lideen Allah Street (Bein Al-Qasrein).

After completing his secondary education, Mahfouz was admitted in 1930 to the Egyptian University (now Cairo University), where he studied philosophy, graduating in 1934.

By 1936, having spent a year working on an

M.A. in philosophy, he decided to discontinue his studies and become a

professional writer. Mahfouz then worked as a journalist for al-Risala, and

contributed short stories to Al-Hilal and Al-Ahram.

The publication of The Satanic Verses revived the controversy surrounding Mahfouz’s novel Children of Gebelawi. Death threats against Mahfouz followed, including one from the “blind sheikh,” Egyptian-born Omar Abdul-Rahman. Mahfouz was given police protection, but in 1994 an extremist succeeded in attacking the 82-year-old novelist by stabbing him in the neck outside his Cairo home.

He survived, permanently affected by

damage to nerves of his right upper limb. After the incident Mahfouz was unable

to write for more than a few minutes a day and consequently produced fewer and

fewer works.

Al-Azhar mosque.

Al-Azhar mosque.Subsequently, he lived under constant bodyguard protection. Finally, in the beginning of 2006, the novel was published in Egypt with a preface written by Ahmad Kamal Aboul-Magd.

After the threats, Mahfouz stayed in Cairo with his lawyer, Nabil Mounir Habib. Mahfouz and Mounir would spend most of their time in Mounir’s office; Mahfouz used Mounir’s library as a reference for most of his books. Mahfouz stayed with Mounir until his death.

Mahfouz remained a bachelor until age 43 because he believed that, with its numerous restrictions and limitations, marriage would hamper his literary future. “I was afraid of marriage . . . especially when I saw how busy my brothers and sisters were with social events because of it. This one went to visit people, that one invited people. I had the impression that married life would take up all my time. I saw myself drowning in visits and parties. No freedom.”

However, in 1954, he quietly married a

Coptic Orthodox woman from Alexandria, Atiyyatallah Ibrahim, with whom he had

two daughters, Fatima and Umm Kalthum. The couple initially lived on a

houseboat in the Agouza section of Cairo on the west bank of the Nile, then

moved to an apartment along the river in the same area.

Mahfouz avoided public exposure, especially inquiries into his private life, which might have become, as he put it, “a silly topic in journals and radio programs.”

The picture of the world as it emerges from the bulk of

Mahfouz’s work is very gloomy indeed, though not completely disheartened. It

shows that the author’s social utopia is far from being realized.

Mahfouz seems to conceive of time as a metaphysical force

of oppression. His novels have consistently shown time as the bringer of

change, and change as a very painful process, and very often time is not

content until it has dealt his heroes the final blow of death.

To recap, in Mahfouz’s dark tapestry of the world there

are only two bright spots. These consist of man’s continuing struggle for

equality on the one hand and the promise of scientific progress on the other;

meanwhile, life is a tragedy.

Mahfouz creates an intricate pattern of verbal irony which he weaves into the very texture of the novel and maintains throughout.

This pattern of verbal irony engenders in the reader an

awareness of the contrast between the object and mode of expression, i.e. the

realistic situation and the exaggerated terms in which it is rendered.

This awareness creates and sustains, all the way through,

a sense of dramatic irony where the reader is cognizant of a basic fact of

which the protagonist is ignorant, namely that his obsession has misguided him.

It is in the creation and sustainment of this pattern of verbal irony, and in the complete subjugation of the novelistic experience to a language order originally alien to it, that Mahfouz has achieved a feat unprecedented not only in his own work but probably in Arabic fiction altogether.

An excellent choice for frequent travelers, this understatedly stylish bag has all options you could possibly need for any trip or commute. With enough room for supplies that you might need for overnight travel.